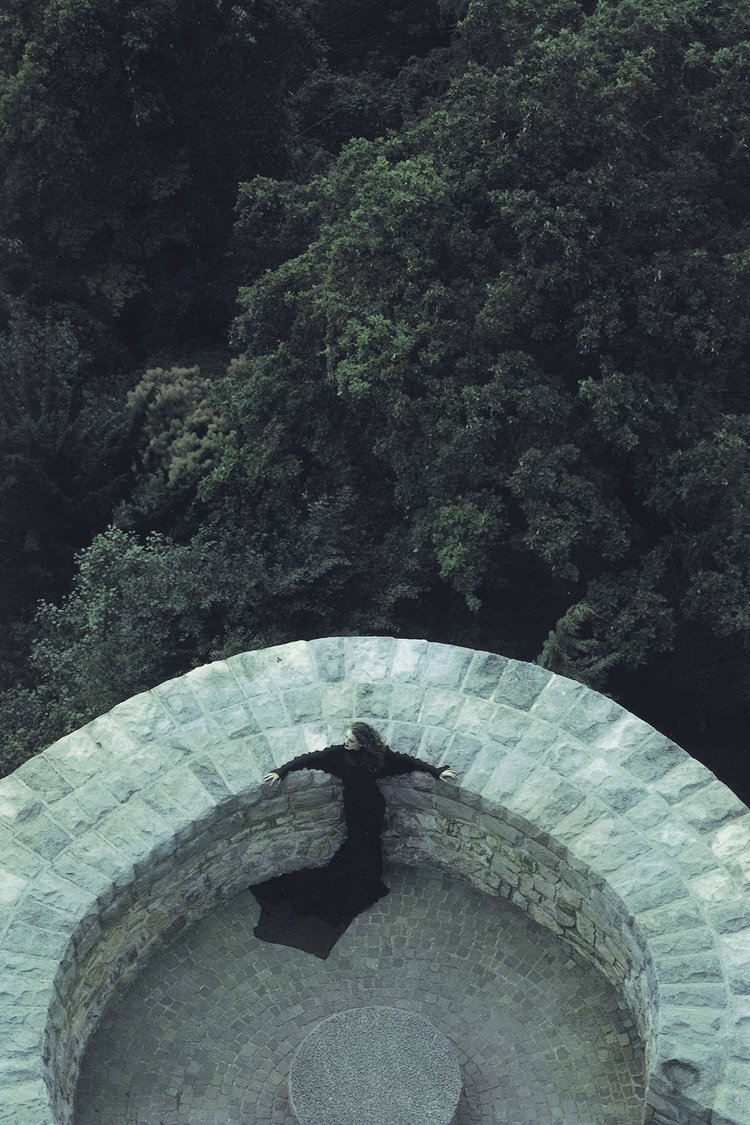

WOODLANDS AND THE LADY OF THE LAKE

October 19 - November 20, 2021

“And into the forest I go, to lose my mind and find my soul.”

Fashion photography has long been enthralled by the forest: an enchanted space where the confines of fast metropolitan living cannot reach, and nature governs all. In the moss-covered refuge of towering trees and the cool depths of glimmering lakes have emerged some of the most compelling images of our time. From ethereal Shakespearean forests and into the woods of Snow White, the woodlands with their transformative bodies of water have always served as a source of escape, discovery, and renewal.

The whimsical regenerative nature of the forest and the mysterious power of the lakes that nourish and surround them have captured the imagination and energized the human spirit for centuries. The mythology of the forest, lakes and its creatures have long been a significant source of artistic inspiration in painting, sculpture, film, and photography as the dark, autumnal setting encapsulates a mood unlike any other.

Woodlands and the Lady of the Lake: Comparing Contemporary Photography with Classical Painting

The mythology of the forest, lakes and its creatures have long been a significant source of artistic inspiration in painting, sculpture, film and photography as the dark, autumnal setting encapsulates a mood unlike any other. There are numerous comparisons to be made between the works of contemporary photographers and classical paintings from history inspired by the aura and subject of the woodlands and lakes.

Classical paintings from the Renaissance period are abundant with imagery of Goddesses and Nymphs bathing in the forest. The enchantment and mystery of the forest with its accompanying lakes and streams provided the perfect location for the Renaissance fixation with mythological subject matter. There is a striking parallel between Rober Farber’s contemporary photograph Two On A Rock, 1979 and some classical paintings of Renaissance masters, including Titian’s Diana and Callisto, 1556-9, Rembrandt van Rijn’s, Diana Bathing with her Nymphs with Actaeon and Callisto, 1634 and Peter Paul Rubens, The Judgement of Paris, 1638. Farber’s glowing female figures, with their nude flesh contrasted against the murky woodland scenery and glimmering stream is largely evocative of the nude Goddesses and Nymphs bathing and frolicking in the ethereal forest scenes of some of the great Renaissance masters. Whilst the subject matter or narrative in these classical paintings are vastly different from that of Farber's, the works bear a distinct visual resemblance to each other. Farber’s style, which has often been described as painterly, is evident through the soft-focus of his photograph which emulates the light brushstrokes and blending of oil paint.

Farber’s photograph draws on a long history of human fascination with the woods and lakes, which serve as transformative spaces that we are attracted to for means of storytelling. There is a certain allure to the forest and its accompanying lakes, the subject of the nude body in the forest generates a sense of mystery and attraction, perhaps due to the collision of two organic forms of beauty. The links between Farber’s imagery and classical paintings indicate the ties between the various media of the arts, culture, history and our society, contributing to a wider understanding of how we interpret the world around us.

There are similar comparisons to be made between Sylvie Castoni’s 2012 photograph L’Inconnu Du Lac, which centres the lake and its mythical beauty as the perfect setting to the scene. Upon a first glance at Castoni’s photograph a sense of similarity formulates, like arriving home after being away or returning to your favourite fall sweater after summer. The image is fresh and beautiful yet also timeless, perhaps because it forms a strong visual resemblance to the famous work by Alexandre Cabanel, The Birth of Venus, 1863. The iconic painting now residing inside the Louvre, Paris, depicts a nude venus outstretched across the waves that she lies weightlessly upon whilst cherubs float above her. The poses appear somewhat identical, both women lie with their arms above their heads, angling their left elbows to the sky in an act of relaxation. The curve of their hips rise above the water's surface, following the peak of their elbows whilst their legs stretch out elongating the body as it spans the water.

Castoni’s stranger of the lake resembles a modern Venus born from the black lake rather than the ocean. Her pale skin strikes a stark contrast against the dark water that swallows the rest of the picture plane. These two images are perfectly matched in their display of the mythology of the lake or ocean, yet vastly different through the role of the female figure. The female nude has historically been an object of desire portrayed through the male gaze, exemplified by Cabanel’s Venut who lies passive on the waves, as if asleep, with her head turned down allowing the viewer to gaze at her without any confrontation. Despite the similarity of poses, Castoni’s female figure, however, is not asleep. Instead she is pictured confidently swimming through the water with her head held up high above the surface, she is an active participant in the image. Castoni’s photograph displays how contemporary fashion photography can draw on historical references to create works of art which are informed by a past visual language and reimagined with the social ideology of the present day.

There are numerous moments in fashion photography such as these that look back at art historical references, whether consciously or not, to reflect on the present day. Through the evocation of cultural understandings of the past Farber and Castoni are able to create new visually powerful works of art that are innovative yet appear timeless to the eye.